[Also posted on Sinopsis.]

Some of the challenges the CCP faces in managing public discourse in democratic societies can be overcome by insulating interactions at the local level. The decentralisation often seen in Western administrations gives local officials high levels of decision power, making them an ideal target for “friendly contact” efforts. Foreign debates over interactions with PRC entities often feature critical views, what writing on propaganda often calls the “China Threat Theory” (中国威胁论), generalising PRC reactions to the use of the phrase in the US in the 1990s. Xi Jinping’s rule features a global expansion of Party work, notably propaganda and United Front efforts that can help engineer environments favourable to CCP policies. The installation of Xiist concepts at the United Nations is a discourse-engineering success story, illustrating the use of multiple state and private entities and methods ranging from propaganda to bribery. Lesser endeavours, such as specific investment projects, have no access to the resources demanded by large-scale discourse management, but are just as relevant to national strategic goals. At the local level, perceptions of the potential benefits of engagement with Xi’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiative are often remarkably optimistic, and knowledge asymmetry can help avoid scrutiny of the more controversial political or military aspects of cooperation projects. In such cases, localisation can let interactions reach successful outcomes within low-level jurisdictions, creating faits accomplis before national media attention can trigger critical (“threat”) narratives.

May the China Opportunity Theory (中国机遇论) defeat the China Threat Theory (中国威胁论). Source: CRI.

The following examples, drawn from Sweden, Norway and Greenland, illustrate the risks posed to localised interactions when information management fails to confine them to the local domain. In all three cases, PRC actors enjoyed a largely positive reception from local decision makers before public scrutiny took them to a more critical discourse environment.

Sweden: a creature of Perestroika Panic guides public opinion

Sweden is a challenging environment for the CCP’s discourse management activities. The media frequently covers Chinese topics with expert insight, including original reporting from China. Public discussion regularly features local China experts, often with critical views on CCP policies. A number of incidents have hurt the PRC’s image. Publisher Gui Minhai 桂民海, a Swedish citizen, was kidnapped in 2015 in Thailand in one of a series of PRC abductions of critical Hong Kong booksellers; he was later released, rearrested and forced to deliver a statement to CCP-friendly media, including Jack Ma’s South China Morning Post. Another Swedish citizen, the NGO worker Peter Dahlin, was detained in 2016 and only released after a staged televised confession. Dorjee Gyantsan (རྡོ་རྗེ་རྒྱལ་མཚན་), a Tibetan refugee recruited by the MSS, was sentenced to a year and ten months in jail in 2018 for spying on the local Tibetan community. Public criticism led to the closure of three of Sweden’s four Confucius Institutes (in Stockholm, Karlstad and Karlskrona) between 2015 and 2016, leaving only Luleå, itself the target of some criticism; a new, less ambitious one is planned in Borlänge, with a small local government rather than a university as partner, and called ‘institute’ despite apparently being expected to cater to secondary-school students, is already controversial.

Gui Congyou, then director of the Department of European and Central Asian Affairs of the Foreign Ministry, at the Russian embassy in Beijing, 2016. Source: Sina.

The current approach to media management, while possibly beneficial domestically, is not improving China’s image in Sweden. A new ambassador, Gui Congyou 桂从友, was appointed in 2017, before which he had never visited Sweden or had any contact with Swedes. After working at the CCP Central Committee’s Policy Research Office (政策研究室) in the early 1990s, his career had a post-Soviet focus: he worked in Russia and at the MFA’s Department for Eastern European and Central Asian Affairs (欧亚司). In 2014, he conveyed to Russian media the PRC’s support for Russia’s position in the Ukrainian crisis. Gui’s formative years at the Policy Research Office amid post-Tian’anmen Perestroika panic and lack of acquaintance with Western media environments (and even the English language) perhaps made him the right person to implement a new set of aggressive media-management tactics to pacify Swedish media. They have failed to yield positive results.

The embassy’s loud responses to unsympathetic coverage, including attempts to smear Gui Minhai and direct verbal attacks against media and journalists, notably Jojje Olsson, have mostly generated negative publicity in Sweden and abroad. Fittingly, Gui Congyou’s PR strategy triggered associations with the former Eastern bloc when a commentator invoked Olof Palme‘s speech calling Gustáv Husák’s repression apparatus ‘minions / henchmen [lit. cattle; etymologically, ‘creatures’] of dictatorship’ (diktaturens kreatur). His Excellency’s attacks on Olsson, whom he advised to rename his website inbeijing.se ‘InChineseTaipei’ to reflect his current residence, failed to silence the journalist, resulting instead in local and international support for him and even prompting a rare Swedish government reaction. The embassy’s campaign to discredit Gui Minhai has only increased support for him, which has included public appeals, demonstrations and, most recently, a book and events at the Gothenburg and Frankfurt book fairs. Last month, the embassy had to perform a lama drama over the Tibetan leader’s latest visit, while solemnly defending a tourist tantrum and fighting a satire show.

These actions are consistent with the intensification of a tantrum-based approach to diplomacy, featuring in-your-face attempts at extraterritorial censorship, from Australia to Denmark and Spain. these activities have proved counterproductive in terms of guidance of public opinion (舆论引导). By triggering constant media discussion of the PRC’s human rights situation and extraterritorial ambitions, such an approach has likely made local public opinion only less favourable to cooperation with China. Xi’s geopolitical initiative could, however, fare better if BRI projects are sheltered from such an adverse media environment.

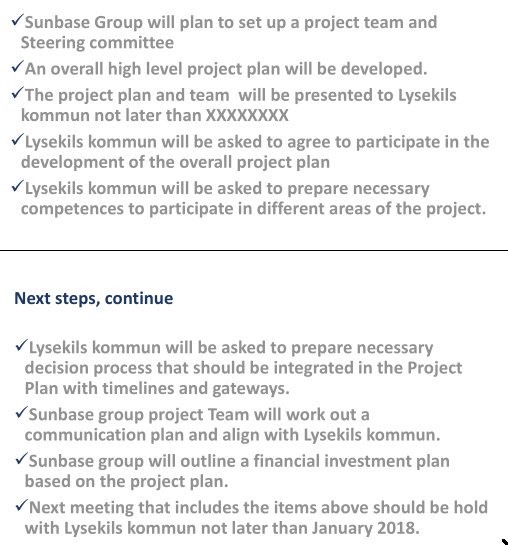

“Lysekina”: a Swedish municipality meets a PLA-linked United Frontling

Last November, officials in Lysekil, a municipality with a population below 15,000, were approached by a group of consultants with an investment plan that included a new deep-sea port, an expansion of the existing one, road infrastructure and even a health resort “with Michelin-star restaurants”. The local authorities were given ten days to respond. They found the proposal “interesting” and commissioned a feasibility study from the same consultants who had proposed it.

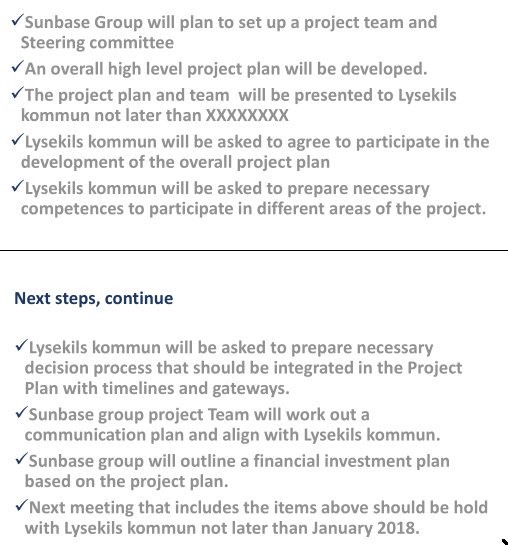

Prompt answer demanded. From the presentation to Lysekil officials. Source: Jojje Olsson on Scribd.

The consultants were representing Sunbase (新恒基, a Hong Kong company owned by Gunter Gao (Gao Jingde 高敬德), with the backing of state-owned China Communications and Construction (CCCC, 中国交通建设). That much was made known to the Lysekil officials.

The consortium’s background was less obvious. Gao is a prominent figure in Hong Kong United Front organisations. He is in his sixth term as a member of the national CPPCC. He was the founding chairman of the Hong Kong Association for the Promotion of the Peaceful “Reunification” of China (HKAPPRC, 中国和平统一促进会). His seniority within UF structures is evidenced by his participation in meetings with high officials, such as Du Qinglin 杜青林, then head of the United Front Work Department, in 2009. Besides his membership in United Front organisations, Gao openly supports the pro-Beijing Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB, 民主建港协进联盟). At a DAB fundraising event in 2016, he paid HK$18.8m for calligraphy (ultimately alluding to a Zuozhuan 左传 passage) by Zhang Xiaoming 张晓明, then head of the Central Government’s Liaison Office, which plays a central role in United Front work and political influence in Hong Kong (Loh, p. 229 et passim). His company used to share an address with eight groups entitled to vote for “functional constituency” representatives at the Hong Kong Legislative Council. Pro-Beijing media channelled his support for the authorities during the 2014 Occupy Central protests.

Gunter Gao as Hong Kong representative at the 8th meeting of the Council for the Promotion of the Peaceful Reunification of China, Beijing, 2009. Source: 中国统促会

Gao has close links to the PLA. As his company’s website puts it, he has “generously supported the publication” of various “valuable books with the intent of promoting the glorious image of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) as a civilizing and a powerful force and of spreading the superior tradition and revolutionary spirit of the PLA”, some published by the pro-CCP Wen Wei Po publishing house and one with a foreword by Jiang Zemin. One of his companies has been managing the PLA’s land in Hong Kong since 1997. Its other customers include the Liaison Office and Xinhua.

The calligraphy specimen by then Central Liaison Office head Zhang Xiaoming that cost Gunter Gao $18.8m at a DAB fundraiser. Source: HK01

CCCC’s role in port building fits within the PRC’s strategic goal of becoming a ‘maritime great power’ (海洋强国). CCCC has been involved in projects in Chinese ports in Gwadar and Colombo. The planned Lysekil investment can be seen as a sign of a more general interest in global port infrastructure. Deep-sea port projects of potential interest to China have been discussed in the Arctic region (Finnafjörður in Iceland and Kirkenes in Norway), although concrete Chinese investment proposals have not yet been made public.

Open media discussion of this background had the potential to derail the project. The consortium’s demand for a quick response from the local authorities suggests they were aware of this risk. Indeed, news about the port plans leaked, leading to local and national media coverage and public criticism. It was nicknamed “Lysekina”, punning on the Swedish word for China. Gao’s United Front and military links were soon brought up, by the author on a microblogging website, and by Olsson (Swedish, English), the journalist later targeted by the embassy’s fury. Concerns emerged about its security implications, mentioning, in particular, the case of the Darwin port in Australia. The ‘China threat theory’ had indeed been triggered.

The prospective investors dropped the project in January 2018. Although it faced other hurdles, such as a landowner who refused to sell or lease, the investors’ representatives cited the public controversy as a reason.

Greenland and the two faces of Arctic propaganda

Greenland has a unique role to play in China’s Arctic strategy. Its mineral deposits match some of the goals of medium-term national planning on mining, specifically concerning rare-earth minerals. The island is an important location for scientific research; senior scientists and officials have repeatedly stressed the national-interest motives behind PRC Arctic and Antarctic science, “directly related to a nation’s ability to turn polar natural resources into commercial resources” (《极地国家政策研究报告》(2013-2014), quoted in Brady, p. 102). Organs under the Ministry of Land and Resources (since restructured into the new Ministry of Natural Resources) have driven geological research in Greenland, also promoting its findings to the mining industry and acting as the Greenlandic government’s main interlocutor. The country’s natural resource needs were invoked by a government-linked think tank promoting the first exploration project in Greenland in 2009, as well as by the research institute behind the only serious Chinese investment in Greenland to date. Plans for a permanent research station in Greenland were seen as a priority already in 2015; one of the locations discussed, at 83°N, would be the world’s northernmost settlement on dry land. Beyond natural resources, the Arctic is central to China’s national defence, both as part of its global maritime strategy and due to the region’s importance for nuclear security, since the shortest ICBM trajectories between China and the US cross the Arctic (Brady, p. 79).

An independent Greenland with China as its main trading partner and investor would be geopolitically advantageous to the PRC. The extreme asymmetry of the relationship could make it relatively easy for China to negotiate for Greenland’s support in discussions on Arctic governance. China’s efforts to cultivate the smallest of the currently independent Arctic states, Iceland, have already yielded a remarkable partnership: Iceland was the first European country to sign a free trade agreement with China and the first to award a Chinese SOE an Arctic oil and gas licence (since relinquished); recent Icelandic contributions towards the CCP’s global discourse-management goals include former president Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson’s praise for aspects of China’s “leadership”, foreign minister Guðlaugur Þór Þórðarson’s China Daily oped last month and a Reykjavik meeting to discuss ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ (or the weather, depending on who you ask) covered on Sinopsis. Given a generally positive attitude towards engagement with China among Greenland’s political elite, an independent Greenland would be even more receptive than Iceland to PRC economic and political influence. Indeed, the current attitude has emerged at little cost to China: despite China’s realistic medium-term potential to become the main investor in Greenland’s mining sector, only one serious investment exists so far, worth less than US$5m.

The PRC’s interests in Greenland are controversial, especially in Denmark. Greenland’s independence would mean the loss of Denmark’s status as an Arctic state. China may become a competitor for influence. In 2016, General Nice Group (俊安集团), a private company that owns an iron mining licence of no significant commercial value in the short term, attempted to acquire a derelict naval base in Kangilinnguit (Grønnedal). The plans were hard to construe as a commercial investment in Western terms: General Nice, a private iron trader plagued by debts and court cases, could hardly want such an asset except, assuming no state entities recommended the purchase, to make itself relevant to national interests as a form of ‘insurance’. The deal, approved by the Greenlandic authorities, was quietly blocked by the Danish government which soon rediscovered the site’s worth as a “strategic and logistical base”. The dreaded ‘China Threat Theory’ emerged in 2013, when controversy over potential Chinese investment in the Isua iron mine led to the fall of a government. A possible bid by CCCC to take part in airport projects generated concerns in Denmark and, reportedly, the US, leading to an agreement where the Danish government will help fund construction work at two airports. The Danish intervention was not to the liking of a junior party in the ruling coalition, leading to the collapse of PM Kim Kielsen’s third cabinet and the formation of a new minority government, still under Kielsen. The second government change caused by discussions of PRC interest was a net win for Kielsen’s government, putting it unexpectedly closer to getting Danish (and vaguely described American) funding for projects the Danish PM was sceptical about not a year ago.

The fact that mere talk of China deals has caused two government changes in a country without much actual PRC investment illustrates the sensitivity attached to China’s interests in Greenland; an awareness of this sensitivity informs the PRC’s messaging. While the Danish government tends to avoid identifying China on the record as a motivation for such moves as the agreement on airports, Danish reporting and analysis widely discuss the PRC’s potential ability to capitalise on Greenlandic independence ambitions, which a local writer sees as “life-threatening” to the Danish realm. The Danish intelligence service openly warns about the implications of PRC investment in Greenland, which could lead to “dependence”. The Greenlandic political elite’s commitment to developing infrastructure projects with uncertain profitability prospects, while actively inviting PRC participation, make discussion of a debt ‘trap’ scenario predictable. (No PRC infrastructure loans to Greenland are known to have been discussed, but Chinese financing is expected for mining projects.) Accordingly, the PRC has been cautious to avoid any perception of support for Greenland’s independence. Protocol arrangements clearly treat Greenland as a subnational entity, at times in contrast to the Greenlandic government’s own communications; when necessary, the Chinese MFA has not hesitated to remind Greenland it “should follow the foreign policy upheld by Denmark”. In China, emerging academic discussion of Greenland’s independence still avoids discussing its consequences for the PRC’s geopolitical goals. Appeals to China’s well-known opposition to a universal self-determination principle are a poor explanation: as Gui Congyou, now the ambassador to Sweden, once told Russian media, the PRC is “against independence declarations by any nationalities through referendums, but this doesn’t apply to Crimea”. Rather, any perceived support would generate opposition, and Chinese non-action (无为而治) can simply let Greenland approach Beijing’s orbit of its own accord. China already buys, by one estimate, around 40% of Greenland’s seafood exports (seafood makes up 94% of the island’s total exports). The head of the Greenland Business Association claims to have discussed the possibility of a free trade agreement with the PRC ambassador during a recent visit to Greenland. After years of opposition from local authorities, Chinese workers were finally allowed last year to work at state-owned Royal Greenland’s fish processing factories. 62 workers had already been hired to work in Greenland as of a few months ago; mining projects will require at least hundreds. Local politicians are often receptive towards cooperation with the PRC; as the fall of the third Kielsen cabinet shows, Danish interests can generate more opposition. A low profile and the proper messaging towards Greenland can continue to increase the PRC’s economic and political leverage with little need for the Party-state to invest actual (monetary or political) capital.

Guidance of public opinion. Source: Guangming Daily.

External propaganda (外宣, ‘exoprop’) turns attention away from Greenland’s importance within PRC policy; this strategy benefits from a lack of expertise on China among prominent commentators. Last January’s Arctic White Paper, a document for foreign consumption, does not even mention Greenland. This is in line with the general duplicity of the PRC’s polar communications towards internal and external audiences, which strictly follow the ‘insiders and outsiders are different’ (内外有别) principle, applied to both endo- and exoprop (Brady, p. 269 et passim). In English-language materials and state-supervised interactions with foreigners, PRC entities stress the country’s interest in scientific research while omitting its subordinate role to national economic and military needs.

The effectiveness of discourse-management tactics is enhanced by a frequent disregard for Chinese-language sources in publications about the Arctic, in what one may call the misère des études arctiques. A lack of Chinese skills (“in Chinese, the word for ‘sea’ literally translates to ‘vast, expansive space’” (misquoting Schottenhammer; cf.GSR 732h, Schuessler s.v. 洋, STEDT #6403, Serruys)) doesn’t deter scholars from discussing “how China sees the Arctic”. The 2018 Arctic White Paper, an exoprop product that mostly reaffirms known policies in general terms, was read as a strategy document and used to draw conclusions about China’s “main policy goals”; in a sign that reactions matched propaganda goals, an exoprop organ relayed Western remarks that the word “military” doesn’t occur in the paper (“and that’s maybe positive”); its discussion of a ‘Polar Silk Road’, by then a years–old concept, was treated as novel (as for my own comments on the paper, they had some innocuous parts plagiarised by the People’s Daily’s English website). One think-tank report derived the “organizing principles” of the PRC’s Arctic policy from the White Paper and the English version of a speech at an international event. Another one, again ignoring original-language sources, overestimated Chinese FDI stock in Greenland by three orders of magnitude; a revised version, published after receiving my (unacknowledged) corrections, gives a smaller, though still erroneous, figure, and its lead author has continued to rely on calculations in which $2bn (overestimated FDI) is 11.6% of $1.06bn (underestimated GDP). While these examples of alternative maths and intellectual laziness are certainly not universal in writing about China and the Arctic, they illustrate the standards of scholarship and analysis in English-language writing about the region. As in other domains, China-illiteracy makes exoprop work easier.

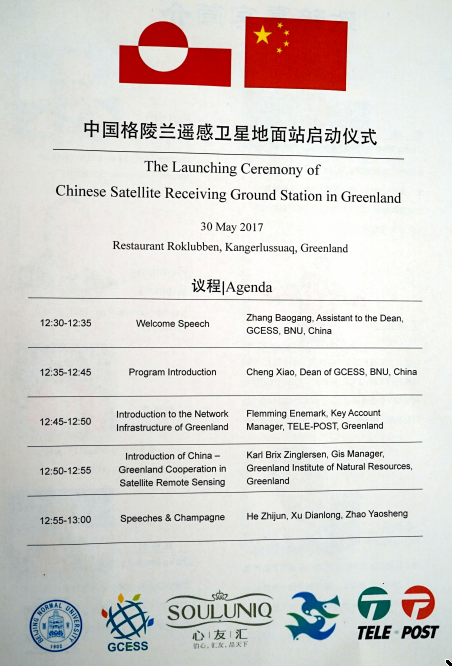

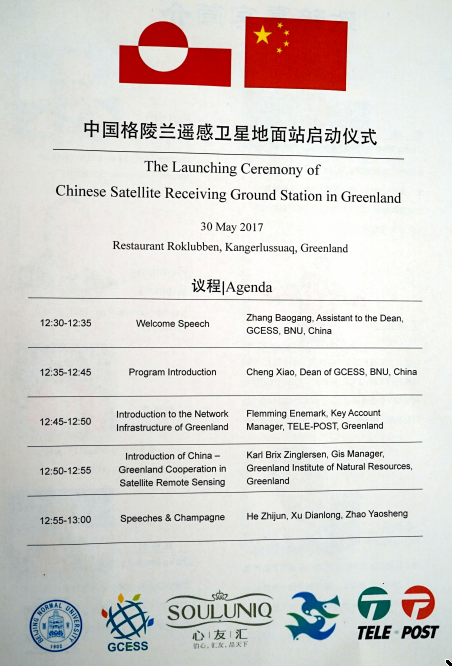

The surreptitious “launch” of a satellite station project

In May 2017, a project to set up a dual-use satellite ground station in Nuuk was “officially launched” on Greenlandic soil. The ceremony was attended by Cheng Xiao 程晓, the leading remote sensing expert in charge of the project, and a hundred Chinese visitors, including retired PLAN Rear Admiral Chen Yan 陈俨, former political commissar of the South China Sea fleet and NPC delegate between 2003 and 2008. A Beidou pioneer with a military background spoke at the event. The trip to Greenland was also used to fly the first Chinese remote-sensing drone in Greenland, the Jiying 极鹰 3. Although these events were reported in Chinese, the Greenlandic government remained unaware of the project months after its official launch. First mentioned in English on my blog, the project’s existence only became known to the Greenlandic public and their elected representatives after it was covered in a story by Andreas Lindqvist for the local paper AG, using my translations from Chinese sources. My full account, including the background of the main individuals in attendance, was posted in December.

The project illustrates the PRC’s double messaging in the Arctic. It was possible to organise a discreet event with a hundred participants in a town with a population of 493 by bringing them as a tour group. After the event, the tourists continued on an eight-day cruise of eastern Greenland. The tour was organized by Souluniq, a high-end tour operator long associated with communicating the importance of the polar regions to China’s national interest. The fact that the Chinese public for the event was a tour group attending this ‘launch’ as a patriotic-themed attraction, after lunch in a restaurant, was not disclosed in Chinese media accounts: indeed, the phrasing allowed readers to imagine a joint ceremony with the Greenlandic government, marking the actual start of the station’s construction. In fact, no date had been fixed for the actual construction of the station, a 7m antenna to be installed outside Nuuk; the required authorisation had not been sought with the Greenlandic authorities. To a Chinese audience, this was the launch of a major project in Greenland; for the locals, it was just another group of Chinese tourists. The project’s local partner saw its leader as just a fellow scientist, a perception that can help the project’s chances with the local authorities. Relevant Chinese audiences, on the other hand, have been made aware of Cheng Xiao’s key role in China’s polar strategy. A global network of satellite receiving stations is of strategic importance to the PRC; in the Arctic, one opened in Kiruna, Sweden, in 2016, to be followed by another one in Sodankylä, Finland. The dual-use Beidou satellite navigation system, in particular, needs more ground stations. The military aspect of the PRC’s polar strategy is clear to Cheng, who warns that “China’s threats come from the Arctic” and, according to a participant, discussed the military significance of the project during the Greenland tour.

RAdm Chen Yan 陈俨 in 2011~2012. Source: 81.cn.

RAdm (Ret) Chen Yan aboard the Sea Spirit cruise in Greenland, after the ‘launch’ ceremony.

This dual-propaganda feat was achieved thanks to a relationship Cheng had built with Karl Zinglersen, a database expert at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (Pinngortitaleriffik / Grønlands Naturinstitut). Cheng offered Zinglersen a satellite map of Greenland, made from American open-source imagery, as a gift, through the PRC Ministry of Science and Technology. Zinglersen had, by his own account, spent “decades” waiting for such a map from the Danish authorities. Talking to the Chinese press, Cheng has explicitly referred to this exchange as an example of engagement with Arctic populations through higher education and research institutions, since as “unofficial” entities they are able to “effectively counter the ‘China Arctic threat theory’.”

Greenland Institute of Natural Resources database scientist Karl Zinglersen receives a satellite map from Cheng Xiao. Source.

Reactions followed reporting on the project’s discreet launch. In Greenland, the chair of the parliamentary foreign affairs and security committee found the surreptitiousness of the launch “a bit worrying,” while warning against getting “scared every time there is a Chinese project.” In Denmark, the head of the Defence College (Forsvarsakademiet) noted that the host government would need to have “full access” to data collected by the station, or otherwise it could “obviously also be used for intelligence gathering and military goals”.

Had it remained confined to the local domain, the project might have proceeded smoothly, perceived as cooperation between fellow scientists, then presented as a fait accompli for the approval of the local authorities. Its exposure, attracting the wrong kind of attention, could complicate its prospects. No further information on the project has emerged since its ‘official launch’ was revealed and it remains unclear when it will be built.

Knowledge asymmetry: all aboard the Shanzhai Choo-Choo

The effectiveness of the localisation approach depends on high levels of knowledge asymmetry. Among local decision makers, a general familiarity with American, European and in some cases Russian society and culture contrasts with a lack of knowledge of and interest in the PRC political system, despite ritual statements on the importance of relations with China. An expertise vacuum also provides a propitious environment for the CCP’s ongoing discourse engineering endeavours: often with CCP-linked support or incentives, think-tanks and other entities can help install a perception of the PRC as a munificent benefactor and the adoption of Xi Jinping’s geopolitical initiative as inevitable. A final Nordic example may illustrate this favourable environment.

Last January, the Värmland-Østfold Cross-Border Committee, an organisation that seeks cooperation between some of the municipalities on both sides of the Swedish-Norwegian border, hosted a Chinese delegation to discuss a possible $21bn investment in a high-speed railway line between Oslo and Stockholm. The host organisation’s leader and its partners are involved in TENTacle, a partnership between government and regional entities in nine countries in the Baltic region that seeks to develop transport infrastructure with EU funding; they often advocate Xi’s Belt and Road initiative. The head of the delegation, Huang Xin 黄新, gave a talk on “Bridging Scandinavia with China through the new Silk Road”. The railway proposal was welcome as an improvement over Norway and Sweden’s disinterest in building “modern railways”; the news was reported in both countries.

Source: Grensekomiteen Värmland-Østfold.

Local prospective partners and journalists without China expertise failed to notice that the proposal came from a “rogue” entrepreneur whose authority to negotiate such a high-profile infrastructure investment was rather doubtful. As was quickly noted on social media, both organisations Huang Xin presumably represented have been reprimanded by the PRC government (he has also been a Huarong employee but wasn’t identified as such in accounts of the Norway visit). One, the China Association for Promoting International Economic and Technical Cooperation (CAPC, 中国国际经济技术合作促进会), which has seemingly been engulfed in a leadership dispute, was suspended for three months in 2017 for the misuse of the terms “civil-military fusion”, “Belt and Road” and “China” by one of its subsidiary entities. A name used by the other one, the China Overseas Investment Union (COIUN, 中国海外投资联合会), occurs on an official list of “rogue” or fake (shanzhai 山寨) entities.

Huang Xin with COIUN boss Zheng Shuai 郑帅. Source: COIUN.

The bubble burst when the issue attracted the attention of national media in Sweden. Hanna Sahlberg, the state broadcaster’s Beijing correspondent, contacted CAPC, who denied even knowing Huang or his Oslo mission.

Cursory due diligence would have raised red flags about Huang Xin: whatever their legitimate activities and evidence of Party-state connections, both organisations he was said to represent seemed to be on the wrong side of the government not long before the encounter; when asked, one of the organisations denied even knowing the envoy. An American or European visitor of unclear affiliation would have hardly been taken as a serious interlocutor for a multi-billion project without further inquiry, and such suspicious signs as the ones surrounding Huang would have probably paused any discussion. Blind faith in BRI prodigality (‘the scattering of monies’), however, makes people forget the need for due diligence.

Influence for free: leverage without investment

The uncritical reception even a seemingly “rogue” entrepreneur can expect from some local partners shows how fertile the ground is for the localisation approach. Especially in societies where propaganda efforts have not yet succeeded in engineering a sufficiently favourable climate, the administrative decentralisation typical of Western countries can be exploited to compartmentalise interactions, confining them to more manageable locales. Although projects like “Lysekina” have faced difficulties once they spilled into the larger media environment, the potential for localised success is clear throughout the region.

In an example of a positive attitude, the head of a company owned by Sør-Varanger municipality in northern Norway, whose seat is Kirkenes, recently interpreted the Arctic White Paper as a sign that “the Chinese state” supports their development “vision”, including long-discussed plans for an “Arctic railway” to Finland that should turn the coastal town into “the Rotterdam of the Arctic”. Local officials have indeed adopted Xi’s “silk road” vocabulary.

The Nordic examples in this piece illustrate the potential of localisation tactics for the success of Xi’s geopolitical ‘Belt and Road’ strategy. The scenario is, however, not specific to Nordic locales. In a French example, Huawei’s ‘smart city’ project in Valenciennes seemed well received locally, with the mayor calling it “a €2bn gift to the city”. Beyond Europe, local government enthusiasm is easy to find, for example, in New Zealand, where an interesting example is provided by the links between Southland Mayor Gary Tong and noted United Frontling Zhang Yikun 张乙坤, noted for his political donations.

A New Zealand council welcomes a local Xiist lobbying group and ‘their’ BRI. Source: NZCC.

In the Nordics, a degree of success is already visible in the form of local-level interest in BRI, even before a concrete case for the initiative as beneficial to local communities can be made based on concrete Chinese plans. The importance of discourse engineering is demonstrated by cases where a reigning perception that Xi and his initiative might bring large investments has been effective in the absence of actual economic leverage. ‘Positive energy’ (正能量) on BRI gives the CCP influence over foreign societies essentially for free. The ‘normalisation’ of Norway, achieved despite the PRC’s inability to exert real economic pressure after the Nobel prize to Liu Xiaobo, remains the best example. A Finnish minister’s nervous hesitation (29:54) when asked if the PRC is a dictatorship during an interview on vague cooperation plans could be a sign of things to come.

In the long term, Xi’s global expansion of United Front and propaganda work should successfully cultivate political and business elites, media entities and, crucially, the next generation of China scholars, in order to engineer favourable environments at the national and European level as well. In the meantime, localisation tactics offer considerable potential for the implementation of Xi’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiative and other CCP strategies.

[Thanks to Chris Button, Magnus Fiskesjö, Andreas Bøje Forsby, Nadège Rolland, Matt Schrader, Geoff Wade and Andréa Worden]