[After the weekend’s election, a slightly edited and updated version of this post appeared on China Heritage, with a must-read introduction and collection of links by Geremie Barmé, to whom I’m grateful for republishing (and helping edit) the piece.]

A report by Anne-Marie Brady of the University of Canterbury, just released through the Wilson Center, gives the first comprehensive description of efforts by the Chinese Communist Party to exert influence on New Zealand politics, business and media. This post focuses on one aspect of Brady’s paper, with considerable overlap with its sources but also some additional details and comments. It’s been written in a rush, whence the generally rambling character and typos.

Skirt lifted, jewels unveiled

This post will eventually resolve into a discussion of the Xi personality cult as embedded in New Zealand campaign slogans; specifically, a slogan with sexual associations that has spawned variations where skirts are lifted and pipes are rubbed. But beyond these juicy details, Brady’s report is about united front activities, and I’d also like to summarise what I see as the essential characteristics of the Front idea. An idea that goes back to the 1920s, but is seeing its most splendid implementation under Xi Jinping.

The title of Brady’s report (“Magic weapons: China’s political influence activities under Xi Jinping”) alludes to a memorable bit of Maoist Scripture, the Chairman’s characterisation of the united front as one of the CCP’s revolutionary ‘magic weapons’ (法宝 fǎbǎo), the others being ‘armed struggle’ and ‘the construction of the Party’. The word fǎbǎo is (I think) first attested as a Buddhist term, a literal translation of Sanskrit dharmaratna. The ‘jewel of the dharma’, one of the Three Jewels of Buddhism, refers to the teachings of the Buddha. The semantic shift to ‘magic weapon’ likely happened in Daoism. Rather than a skirt, the Brady report lifts the veil on Xi’s reactivation of Mao’s weaponised jewel.

Although focused on New Zealand, Brady’s report discusses the CCP’s United Front (统一战线) tactics in general. The idea goes back to early Communism, whose theoreticians talked of the need for strategic alliances with other parties and movements as a preliminary stage to a Communist takeover. After its role in the Bolsheviks’ rise in Russia, the concept was adopted by the Comintern in 1921 at Zinoviev’s initiative. The name was already ‘united (workers’) front’ (единый (рабочий) фронт). The Comintern language of those days talks of joining forces with other ‘working class’ forces, meaning various factions in the socialist movement, by then split into a variety of groups within which Soviet-loyal Communists were often a minority. A Comintern appeal from 1922 calls for those who haven’t yet made up their minds to take up arms and struggle for “power” and “dictatorship” to “at least unite in the struggle for ordinary subsistence” against “exploiters and traitors to humanity“. The harangue is directed to all working class representatives, be they “Communists, Social Democrats, or Anarchists, or Syndicalists”. That sounds like building alliances, but a key aspect is that the Communist movement saw these tactics as temporary, intended to eventually give it hegemonic power. The Communist Party intended to stay separate from reformists or Anarchists it ultimately saw as their ideological enemies. The first ‘united front’ was essentially about instrumentalising European Social Democrats in the 1920s; later on, these alliances would become narrower (shedding the Social Democrats under Stalinism), then broader (the ‘Popular Front’ with ‘bourgeois’ forces against Fascism) and later discarded altogether after Stalin’s pact with Hitler.

But there’s more to united front strategies than temporary alliances with working-class forces to the left or right of Soviet-style Communism itself. The instrumentalisation doesn’t have to stop at these notional ideological allies within the socialist spectrum. Brady’s report quotes from Lenin’s The Infantile Sickness of “Leftism” in Communism (Детская болезнь “левизны” в коммунизме), a 1920 tract where he attacks Western European Communists farther to his left. Although the work doesn’t literally mention any ‘fronts’, the tactics it describes subsume their description by the Comintern one year later as a particular case. Beyond the alliances with socialists and trade unionists mentioned the appeal quoted above, Lenin advocates tactical cooperation with ‘bourgeois’ organisations: it’s only possible to “vanquish a more powerful enemy” by “skillfully using […] opposing interests between the bourgeoisie of different countries” and between different bourgeois groups between each country, “as well as every, even the smallest, opportunity of gaining an ally0.” (From this Russian version.)

Lenin devotes an entire section of the tract to the question “[Should we] participate in bourgeois parliaments?” (Участвовать ли в буржуазных парламентах?). Lenin’s ‘infantile’ leftist adversaries would answer in the negative. But for Lenin, parliamentarism has become “obsolete” only “in the propaganda sense”, which somehow also means in the “world-history sense”; its “era” has ended. In practice, it’s not “politically obsolete”, it’s still there, so it should be used. Communists should participate in elections, with the purpose of awakening the “backward strata” (осталные слои), the “ignorant rural masses” (тёмная деревенская масса).

United-front tactics for China began in the 20s, with the Communists’ alliance with the (then much stronger) Kuomintang against warlords. The KMT saw this alliance as a way of controlling the emerging Communists, something they didn’t succeed at and led Chiang Kai-shek to purge the leftists in 1927. The idea was refloated later, to fight against the Japanese invasion. From the beginning, recognising the Chinese Communists Party’s weak position, the Comintern favoured playing united-front with the Chinese ‘national bourgeoisie’. Here’s what Stalin had to say on the topic in 1927, when Chiang turned against the Communists marking the end of the ‘first united front’. In a speech to the plenum of the Party Central Committee1, he talks of three “stages of the Chinese revolution”: the first one, already completed, was the “revolution of the nation-wide unified front”; the “bourgeois-democratic revolution”, then underway; and a “Soviet revolution”, still to come. The speech was summarising an earlier article in Pravda2, where Stalin differentiated between the need for an alliance with the entire KMT in the first, accomplished, stage, and the current situation, where the left wing of the KMT should be used against the right: in the ongoing “struggle between the two paths of the revolution” (its continuation or “liquidation”), “the revolutionary Kuomintang in Wuhan” would “become in practice an organ of the revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry”.

People’s Daily, Dec 18, 1949 via Renmin wang

After Stalin’s ‘third stage’ finally succeeded in 1949, the united front (统一战线 tǒngyī zhànxiàn or 统战 tǒngzhàn for short) took on other forms. Brady mentions the use of ‘foreign friends’ for informal diplomacy and what would become a central aspect of the PRC’s united front work, the control over ethnic Chinese communities abroad. Though culturally and politically diverse, and in the past often hostile to the CCP, by and large diaspora communities have become dominated by PRC-friendly organisations after decades of united front work. Such control over media, business and cultural organisations, as well as over elected representatives in local democratic institutions, creates a strong pressure to acquiesce to PRC policies and views. Once the diaspora is ‘tamed’, its organisations can be repurposed to advance China’s broader policy agenda on the next level, that of mainstream politics, business and media abroad.

In the PRC, the united front isn’t just the name of a political concept. It’s a Party organ of ‘full-ministry rank’ (正部级), the United Front Work Department (shortened name: 统战部 Tǒngzhàn bù) directly under the Central Committee, with offices at the Party committees of lower levels of administration. It speaks volumes about the level of knowledge of the politics of a world power in the Western press that the name of the organisation and policy are is put in (scare?) quotes. An example is this NZ Herald story about Brady’s report. Another is a hilarious incident in which Chau Chak Wing 周则荣, an Australian-Chinese businessman whose political donations were discussed in an ABC-Fairfax investigation, threatened litigation in a letter stating he “has no knowledge of an entity referred to […] as the United Front Work Department”. Australian journalist Alex Joske promptly provided pictures and an official account of a meeting Chau had with district-level United Front officials, not a year before his ‘lack of knowledge’ of such an entity. This is like referring to the ‘Culture Ministry’, or an alleged US ‘State Department’, or the so-called ‘Republican Party’. Like Mike Flynn denying the knowledge of ‘such an entity as a Russian embassy’. There’s nothing secret about the UFWD, and learning about it demands no Sinological prowess. Writing about it is widely available in English (Groot, Angliviel de la Beaumelle…). Those of a more investigative disposition might even try visiting the UFWD’s website. Media powerhouses equipped with so-called ‘telephones’ could even try calling +86-10-58335141 during Beijing office hours (international rates might apply).

United front work has intensified under Xi. Besides its usefulness for international policy purposes, as discussed by Brady, domestic UF organisations, such as the ancillary parties, can be used to handle ‘new social strata‘. This term mostly refers to private businesspeople, which the Party wants to control and reward but not massively incorporate into its ranks. Another example is the clergy of the institutional religions, whose management, training, ‘Sinification’ and instrumentalisationare key united front tasks; monks and priests are supposed to be subservient to the Party, but can’t be admitted into it.

This is another key aspect of united front work. From Lenin onwards, its purpose has not been to proselytise, or form a majority under an ideological consensus, as might be the goal of other political or belief-based organisations. As the history of the united front shows, ideology is simply a tool; state Communism has sought alliances with the Western centre-left, later only with orthodox Communists, then with a broad ‘bourgeois’ arc reaching past the centre, and then directly with Nazism; or, in the Chinese case, with the entire Kuomintang, then only its left wing, later foreign leftists, assorted brands of non-Soviet Communism, and finally a variety of foreign politicians willing to collaborate with its initiatives. Whatever ‘Communist’ might mean to those identifying as such in other countries, the Chinese Party of that name is not primarily an ideological organisation. The country it controls has been through various economic policies which might not be to Marx’s liking. Once, links were sought with Western Communists; nowadays the foreign Far Left is mostly irrelevant to the CCP’s interests, and mainstream ‘bourgeois’ parties are actively cultivated, as exemplified below. Religion, the ‘opium of the people’, its another set of belief systems it commodifies. It does not wish to build an ideological majority, the way a democratic political party would; it simply strives to maintain and extend the power of a stable, centralised, hierarchical organisation, over time, territory and resources. It chooses who can join it; other useful entities and individuals it doesn’t wish to formally phagocytose are controlled (mainly) through the united front organisations.

So that’s the United Front in a nutshell. An official Party organisation, with buildings, phone numbers, publications, that instrumentalises non-Party entities for advancing the goals of the Party-state, within China, in territories China fancies but doesn’t administer, and abroad. The ‘abroad’ part is what Brady’s work is about, and New Zealand is but one case.

Brady’s report covers several areas of United Front influence building in New Zealand, including media (something I’m reserving for some later writing), politics, business and their intersections. In this post, I’d like to mention a few details about the politics part. One reason is that this aspect hasn’t received a lot of attention globally (UF-linked political donations in Australia being an exception). Another one is that there’s a general election in New Zealand in a few days, and the way revelations about certain candidates have been received is revealing in itself. For the record, I have no horse in that race, and will discuss candidates from both major parties.

All roads lead to Xi Dada

New Zealand provides an example of successful United Front domination of a diaspora community. As of this election, the top ethnic Chinese candidates are linked to CCP organisations and support PRC policies. In New Zealand, the Chinese community can only realistically aspire to political representation by its own members through individuals approved by Beijing. This situation, enabled by the leaders of the top parties, effectively allows the extraterritorial implementation of PRC policy.

The most visible ethnic Chinese politician in New Zealand is Yang Jian 杨健 of the National Party. Yang is currently an MP and will almost certainly continue to be after Saturday’s election. With Yang, the Nationals (currently in government) consistently command a majority among the ethnic Chinese electorate some 50% above their overall polling.

Last week, an investigation by the Financial Times and local media Newsroom revealed Yang’s background in military intelligence. He studied and then taught English at the PLA Air Force Engineering Academy (空军工程学院, since renamed University 空军工程大学), and later again studied and worked at the Luoyang Foreign Languages Institute (洛阳外国语学院), a PLA intelligence school. Yang denied ever being a spy, although he admitted his students at Luoyang used the English he taught them to “collect information” about the communications of other countries; “if you define [it] that way, they were spies”.

Yang seems to have hidden his military background from public English-language sources until 2012, once he was already an MP. He said he didn’t mention his studies and career at those PLA institutions in his citizenship application, naming instead civilian partner universities which weren’t his actual place of work. By his own account, such less-than-factual statements were a requirement of the Chinese government if he was to leave China, although he had left that country years before. “It was required by the system,” he said in a Chinese-language interview. “There was nothing I could do.” Another reason not to make his background known was that “people might not understand“, because “the Chinese military system is complicated.” A desire to protect the public from exposure to complicated issues was also perhaps his admonition to a journalist not to write too much about his personal background, as he was recorded saying.

In the same Chinese-language interview quoted above, Yang says he used to be a Communist Party member, but he isn’t one any more. That presumably means ‘not an active member’; as Brady notes, you don’t just ‘leave’ the CCP. You are considered a member unless expelled. Considering Yang’s excellent relations with Chinese state entities and the praise state media award him, it would be ridiculous to assume he was expelled. In all likelihood, Yang is in fact a CCP member. Chen Yonglin 陈用林, a former PRC diplomat who defected to Australia in 2005, cast further doubt on Yang’s claims he was a PLA ‘civilian officer’. Based on his knowledge of military institutions before reforms in the late aughts, Chen estimates Yang was in fact a ‘soldier’ and probably reached the rank of captain.

While a student in Australia, his first foreign destination before moving to New Zealand, Yang was active in the predecessor of the local Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), another organisation with strong state links. Alex Joske and Philip Wen have written about the Australian CSSA.

Media reports claim the New Zealand intelligence service has been looking into Yang’s background.

The case has also attracted the attention of the Chinese government. At the regular MFA press conference, a spokesperson managed to say they wouldn’t comment on the internal affairs of other countries, and then add that reports by the ‘relevant media’ are irresponsible. Pari ratione, Yang Gate is not purely an ‘internal affair’ of New Zealand, which actually makes sense.

Remarkably enough, the National Party defended Yang after these revelations, claiming they were actually aware of his background in military intelligence. Yang is a valued fundraiser for his party (I mean the Nationals, not the CCP). The Nationals claim Yang was properly vetted back in the day, but the company they say they hired to conduct the vetting deny that ever happened, then said they ‘interviewed’ him once. Cutting through the blather, the vagueness in all these statements make it hard to believe senior Nats understood what sort of work was done at the institutions where their main Chinese MP spent more than a decade.

Perhaps even more remarkably, despite what an external observer would see as devastating evidence compromising a candidate before a tight election, his direct political adversaries in the Labour party produced absolutely no criticism of Yang. I’m not terribly knowledgeable about NZ politics, so perhaps I’m being naive, but is it normal to have such a major security revelation on a senior political figure days before an election and hear nothing from his rivals?

The leader of New Zealand First, a minor right-wing party, is so far the only politician calling for an inquiry into Yang’s case.

Other commentators have criticised Yang: Rodney Jones called for his resignation. Michael Reddell talks of a ‘cone of silence’ about the presumably explosive revelations about Yang possibly related to the CCP influence throughout the NZ political establishment described in Brady’s paper.

Reddell also reports a rather shocking development. Chris Finlayson, NZ’s attorney general and the minister responsible for intelligence, was asked at a (rather congenial) candidate meeting about Yang’s case. His answer: “I’m not going to respond to any of the allegations that have been made about/against him. I think it is disgraceful that a whole class of people have been singled out for racial abuse. As for Professor Brady, I don’t think she likes any foreigners at all.” A former student of Brady’s happened to be at the event and forced Finlayson to apologise.

Here are some captioned images of Capt. (alleged) Yang in martial poses and having a good time with his comrades in arms at a PLA anniversary gala, courtesy of my Twitter account.

Dilectus centurionum

Bonum vinum laetificat cor hominis

Divide et impera

The Frontling omertà

In theory, Yang Jian’s direct adversary should be Raymond Huo (Huo Jianqiang 霍建强), a Labour Party MP. Yang and Huo compete for the Chinese-community electorate; Yang has been found to have a background in military intelligence, which he had declined to disclose in the past; Huo, whatever his sympathies, isn’t tainted by work for a foreign military. Recent polls have put Huo’s party a few points short of unseating the Nationals, or even able to lead a coalition. How can he not use this?

The only explanation that makes sense (and that is consistent with reactions from other senior politicians) is that he wouldn’t like to speak up against United Front interests.

Raymond Huo raised some eyebrows some time ago when he began using a Xi Jinping quote as the Chinese version of Labour’s campaign slogan “let’s do this!”:

The Chinese phrase, 撸起袖子加油干 lū qǐ xiùzǐ jiāyóu gàn, means “roll up [our] sleeves and work hard”. Its current popularity stems from its use by Xi Jinping at the latest new year address (8:44). Victor Mair discussed the phrase in extenso on a Language Log post, to which I contributed a few details.

A similar phrase wouldn’t be a bad translation of the Labour slogan, were it not for the obvious Partyspeak association. The specific choice of words (which is what makes it an unmistakable Xi quote) is slightly problematic, namely regarding the first character, 撸 lū. As Mair notes, this isn’t the most common way of saying ‘roll up your sleeves’ in the standard language (that would probably be 卷 juǎn). Xi chose to use a Northern colloquialism, rather dissonant with the style of official speeches, probably attempting to sound folksy. The choice isn’t very effective, and probably wasn’t really thought through, by Xi or his speechwriters. Besides ‘roll up’, 撸 lū means ‘rub’, and brings to mind a slang word for male masturbation, 撸管 lū guǎn ‘rub the pipe’. And not just in my dirty mind; it’s easy to find online attestations of puns on the phrase (挽/卷起袖子加油撸起 ‘roll up your sleeves and rub it’, 撸起管子加油干 ‘rub the pipe and get at it’…).

I refer you to Mair’s post for a case where punning on the phrase led to the dismissal of an official (‘Comrades, “hike up your skirts for a hard shag‘). In its modified form, 撸 lū ‘roll up; rub’ becomes 撩 liāo ‘lift’, and 袖子 xiùzi ‘sleeves’ becomes 裙子 qúnzi ‘skirt’. It should be clear that the slogan is just asking for salacious punning.

The fact that 撸 lū is a Northern regionalism is also telling. The verb is largely limited to Northern forms of Mandarin. Indeed, it’s one of a set of ‘physical action’ verbs whose pronunciation can’t be traced back to Middle Chinese (the common ancestor of Mandarin and most other modern Sinitic languages). Though widely understood, the word is likely to be felt as regional by many, possibly most, Chinese speakers in Huo’s constituency. There actually happen to be many ways of saying ‘roll up [sleeves]’ in Chinese; besides 卷 juǎn, there’s 翻 fān, 折 zhé, 挽 wǎn…

Xi certainly didn’t coin the 撸 lū phrase, but since he uttered it has become associated with him. Just try googling it: recent results are overwhelmingly about the Party slogan. It has has been painted on walls, printed on banners. Articles, songs, enactments, dance performances have been devoted to it. All that in Party-state contexts; jokes and memes emerged in less official venues. Anyone who follows Chinese media will understand that the slogan is pure Partyspeak, an artifact of the cult of personality.

A performance with Xi’s slogan in the background. Source: 苏州市人力资源和社会保障信息中心.

After Brady’s report came out, mentioning the Xi-quote slogan, Huo defended the translation, calling it an “auspicious Chinese idiom that is known widely by Chinese constituents”; given how well it resonates, “it is no surprise that Xi Jinping also used this idiom in his New Year Greeting”. So, this is something lucky we say in New Year, its use by Xi is a mere coincidence, you don’t understand. Echoes of Yang’s ‘complicated system’ above the public’s intellectual abilities: everything Chinese is abstruse, exotic, inscrutable to the general public and better left alone. Needless to say, there’s nothing “auspicious” about the idiom; if anything, it has the same go-getting, gung-ho connotations as ‘roll up your sleeves’ in English. That has nothing to do with “auspiciousness”, and there’s nothing uniquely Chinese about it. The need to roll up your sleeves before doing physical work is familiar in many other sleeved cultures. But in the middle of this bizarre appeal at exoticness, Huo actually confirmed the Xi allusion is what it is: “[m]y team tested this translation among many in the New Zealand Chinese community and this quote stood out as the best one” (my emphasis). So it’s not just an ‘auspicious’ idiom, it’s an actual quote.

As for where Huo got the idea, or which ‘community members’ he tested it on, that’s a bit hard to establish, especially because its use was rather short-lived; Huo seems to have stopped using it after floating it on Twitter and being questioned on why he was quoting Xi. An early-August report by local outlet Skykiwi (天维网), reproduced by PRC state media, has Huo quoting the slogan. An earlier use of the idiom can be found in a Guangming Daily story from April, an interview in Beijing with John Hong (Hong Chengchen 洪承琛), a member of the New Zealand Belt-and-Road Promotion Council (新西兰“一带一路”促进委员) with government contacts in Fujian province (Brady, p. 39). In an opening typical of reporting on the government’s successes, the article quotes Hong as praising the prospects brought about by the signature of a Belt-and-Road agreement with New Zealand, thanks to which “we will also roll up our sleeves and work hard” (我们也要撸起袖子加油干). The key word is “also”: it’s understood that, after Xi’s new year injunction, “everyone” in the PRC is rolling up their sleeves; Hong means now New Zealand will join them. Huo is himself an ardent proponent of New Zealand’s participation in Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative, as will be seen below.

In short, Huo chose a phrase that clearly alludes to the personality cult of an authoritarian leader as a campaign slogan for a major party in a democratic election, and dropped it when called out on it.

When I first learnt about the slogan, it took me some time to realise it wasn’t a joke. My first reaction was that the ‘Raymond Huo’ Twitter account it was promoted through was fake, and that the picture was an attempt to discredit him by associating him with the CCP. But not only Huo was indeed behind the translation; parroting Partyspeak is actually entirely consistent with his activities and advocacy.

Huo has established a New Zealand OBOR Think Tank and a New Zealand OBOR Foundation, devoted to “help promote the idea and educate New Zealanders on the One-Belt One-Road initiative”. It has “linked up with China’s National Development and Reform Commission, as well as Chinese construction companies and private equity firms to look at opportunities.” Huo’s Belt-and-Road advocacy was widely reported by Chinese government organs, such as the State Council Information Office and the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese (全国归国华侨联合会), a United Front organisation.

The establishment of Huo’s Belt-and-Road shop is seen as pretty significant by the Chinese government: its establishment was ‘witnessed’ by the general consul in Auckland and no less than two visiting provincial governors (of Henan and Hubei).

As is typical of united-front activities under Xi, this isn’t simply a Labour Party affair: the think tank is led by Huo together with Johanna Coughlan, sister-in-law of the current PM, Bill English (Brady, p. 40). This achieves a wonderful success for United Front efforts: support for the PRC’s policy goals is embedded in both major parties. Whoever wins in New Zealand elections, Xi’s geopolitical agenda can count on their support.

Huo is far from denying the existence of PRC influence in New Zealand. His views are clear: a Radio NZ story on Xi Jinping’s 2014 visit quoted him as asserting that the Chinese community is “excited about the prospect of China having more influence in New Zealand“, and that “many Chinese community members told him a powerful China meant a backer, either psychologically or in the real sense.”

And here’s Huo’s understanding of how the Chinese community is meant to be represented (from a speech delivered to the NZ China Society): “Advisors from Chinese communities will be duly appointed with close consultation with the Chinese diplomats and community leaders.”

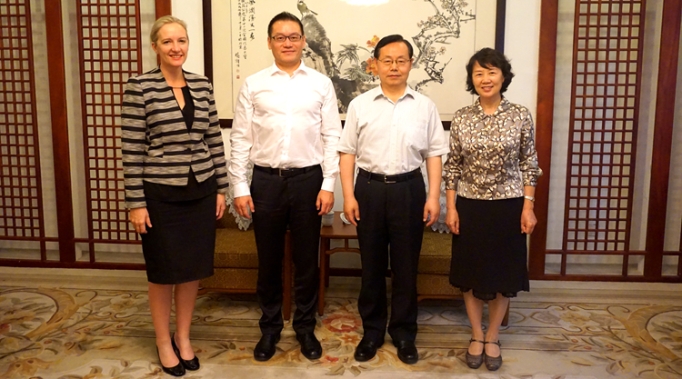

Huo is from Anqing 安庆, Anhui, perhaps the basis for his contact with another Anqing native, Jiang Zuojun 蒋作君, a prominent figure in the Zhi Gong Party 致公党 (one of the ancillary parties to the CCP). Jiang has held many senior government posts, although always at a ‘vice’ level as befits someone from an ancillary party. He has been vice-minister of health, deputy secretary of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, vice-governor of Anhui. The Zhi Gong Party typically liaises with overseas communities for United Front Work purposes, as evidenced in this meeting between Jiang and Raymond Huo on this Think-Tank-cum-Fund. An official account of the meeting, originating from the Zhi Gong Party and published on the website of the Central United Front Work Department, quotes Huo as emphasising “the unique function overseas Chinese have in disseminating” the Belt-and-Road concept (海外华侨华人对于宣传“一带一路”的独特作用).

From the right: Zhi Gong Party Liaison Dept Head Xu Yi 许怡, Jiang Zuojun, Raymond Huo, Johanna Coughlan, NZ prime-ministerial sister-in-law. Source: Central United Front Work Department.

And here’s a final picture of Huo, taken during a visit to Anqing “at the invitation of the City’s Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese”:

Source: Anqing City United Front Work Department

It should be sufficiently clear that Huo is another United Frontling. There’s nothing surprising about his incorporation of Xi’s personality cult into electoral politics, or his silence on the revelations on Yang Jian’s background. Regardless of his views on non-China related issues (which do indeed differ from the National Party’s), Huo isn’t Yang’s opponent as far as the CCP agenda is concerned. For united-front purposes, Huo is simply an egg in another basket.

By focusing on two key individuals from both sides of New Zealand politics, I intended to show how successful united front tactics have been in ensuring permanent control of the Chinese community politics by hedging against democratic power shifts. This is only one of its successes. I refer you to Brady’s work for an overview of the extent of its penetration in politics beyond the Chinese diaspora, business and media. Its pervasive character helps explain why the reaction to the Yang case was so muted, suggesting a ‘code of silence’, with the most senior figures in the major parties essentially glossing over the problem.

The terms in which Brady’s work is being discussed by politicians and the media reflect little understanding of what’s going on. The Yang case made for great headlines that tried really hard to use the word ‘spy’, but he might successfully argue that he is not literally a spy. And even if he was, spying on each other is something countries do. Other UF-linked individuals mentioned in Brady’s report are even less likely than Yang to have been involved on literal espionage. The Brady report isn’t about finding spies. Reactions seem to be addressing a straw-man. Raymond Huo, the Xi-quoter, denied “insinuations against his character”, but it’s not clear that any have been made. If anything, Huo is consistent in his support for CCP policies and increased PRC influence. This is not a spy thriller, but a story about the institutions of a democratic country being coopted to serve the agenda of a much larger state ruled by an authoritarian regime. Most of the people involved might very well have acted legally at all times, and their support for certain policies isn’t necessarily an issue of moral ‘character’. The issue is whether the actions of many in the NZ elite are a risk for the country’s security, independence and democratic system. The latter has obviously been damaged. Restricting attention to the Chinese community, democratic politics has been vitiated to effectively allow extraterritorial control by the CCP and deny voters a true choice of political representation. The intersection of each of ‘National’ and ‘Labour’ with ‘Chinese’ is firmly under the aegis of the United Front. Perfunctory reactions from top politicians are a sign that UF successes aren’t limited to that community. Such control over an advanced democracy is something the united-front pioneers in the ’20s and ’30s could hardly have predicted.

Notes

0 The English translation Brady quotes (from a 1950 edition) says a ‘mass ally’; ‘mass’ is missing in the version of the Russian original published on marxists.org, which is what I used for the translation above. Another Russian edition, available on maoism.ru, matches Brady’s English, ‘mass’ and all. I couldn’t immediately find which specific editions the texts come from, but at least the one on maoism.ru comes from a later edition, as the footnotes show; that’s why I chose to quote from the ‘mass’-less version. Its unclear if the interpolation is Lenin’s or someone else’s, but the difference is immaterial. The English translation (with a more idiomatic title than the one I quoted, used in the first English translation from 1920) is generally faithful to (its version of) the Russian. I’ll try to remember to update this note if I ever happen across a physical Russian edition of Infantile Sickness.

1 Международное положение и оборона СССР: Речь на объединенном пленуме ЦК и ЦКК ВКП(б) (The international situation and the defence of the USSR: Speech at the joint plenum of the Central Committee and the Central Control Commission of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)), Aug 1, 1927. Both Stalin texts from the collected works edition reproduced on Mikhail Grachev‘s website, translations mine.

2 Вопросы китайской революции: Тезисы для пропагандистов, одобренные ЦК ВКП(б) (Issues of the Chinese revolutions: theses for propagandists, approved by the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)), Pravda, Apr 21, 1927.